I love Oscar Wilde.

As a student, I studied his works at university; as a

teacher, I've taught his works to senior pupils. My first ever published comic even

featured Wilde's lover, Bosie, as the time-travelling companion of a particularly

rum Doctor. I've always admired his insight, humanity and sometimes misguided

courage, not to mention, of course, his revelatory wit. But it wasn't until The Psychedelic Journal of the Wild West that I finally attempted to write the man

himself.

When the Journal moved from being solely about time-travel

to focusing on a different genre per issue, I was intrigued. I hadn't written

anything for at least a couple of issues of the comic - I'm not sure I had

anything else to say about time travel at that point - but the Wild West

brought fresh inspiration. At the time, I was fully immersed in the world of

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (not as many middle names as Picasso from

'Martillo', but pretty memorable nonetheless) as I'd recently been teaching his

plays to an Advanced Higher class. I knew Wilde had toured America in 1882,

somewhat quixotically attempting to make the aesthetic movement the basis for

this fresh civilisation's development, so he seemed a perfect fit. Thus 'Wilde Wild West' - its name a nod, of course, to the 60s spy-fi show - was born.

From the off, I wanted to get away from the idea of the

laconic Eastwood-y cowboy type: Wilde's verbose nature was a perfect fit for my

notoriously dialogue-heavy yarns. Indeed, much of Wilde's dialogue in the story

is either a direct quote from one of his works, or at least a modified version

thereof. I wasn't going to kid myself I could write with Wilde's incomparable talent,

so it seemed best to hew closely to his actual words if I were to do him any

justice.

I of course wanted Wilde to deal with something derived from

Native American mythology - there's nothing I like more than delving into the

folklore of a specific region and borrowing its monstrous denizens for my

nefarious purposes. My first thought was to put Wilde up against the horrible

Baykok, a foul emaciated Chippewa demon, that shoots men with invisible arrows,

beats them to death with a club, and then eats their liver (not necessarily in

that order.) I've always wanted to get the Baykok into something, every since I

first read of the awful thing as a child, in Tom McGowen's 'Encyclopaedia of

Legendary Creatures'. (See similar remarks on the phantom black dog from a

recent Spencer Nero tale.) But this wasn't the right place, and I didn't want

to diminish the creature's horror by having it fall victim to Wilde's wit.

Besides, as a man and a writer, Wilde was firmly on the side of redemption, and

the Baykok seemed rather hard to redeem.

Unlike the Rolling Head.

Coming upon this Cheyenne tale of a discombobulated fallen

woman (slain by her husband for an affair with a river spirit, served up to her

children for dinner, and then subsequently reanimated as a vengeful cranium),

it struck me how easy it would be to shape her into a Wildean figure. Wilde

loved women (well, to write about, anyway) and women with a past particularly fascinated

him. Mrs. Erlynne from 'Lady Windermere's Fan' and Mrs. Cheveley from the

brilliant 'An Ideal Husband' are two perfect examples of Wildean femmes who

successfully reinvent themselves and find different ways to regain a place in

the world of respectability. Therefore it struck me that Wilde's solution to

the problem of the Rolling Head had to follow similar lines - he had to find a

way to reintroduce her to society. In 'An Ideal Husband', Wilde wrote that "Sooner

or later, we shall all have to pay for what we do," but also noted that

"No one should be entirely judged by their past." I like to think my

story follows this logic to the letter.

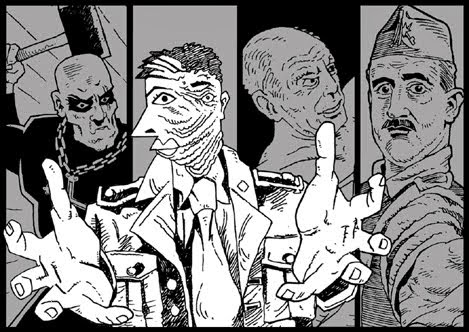

This was the first story of mine Scott Twells ever worked

on, and he was a revelation. I was immediately drawn to the way that his panels

are all framed within the expanse of a larger one. His art here is a mixture of

rustic and cartoonish, his scratchy linework and expert grasp of perspective making

him the perfect fit for the tale. Since then he's drawn many other stories I've

written, and there'll hopefully be more to come in the future. A shout-out goes also to Andrew Scaife for his sterling job on the lettering.

Here's a few page-by-page comments:

Page 1:

- Wilde is wearing an artificially-coloured verdigris carnation throughout the story: he loved the idea of the artificial, and believed nature should imitate art. When I wrote this story, I didn't know if it would be illustrated in colour, but in retrospect, I'd have quite liked if the green carnation had been the only piece of colour in the story.

Page 2:

- Wilde really did go to Leadville to lecture on the early Florentines - this is memorably depicted in the film 'Wilde', starring Stephen Fry, where he gets a very positive reception from the miners. In real life, Wilde was particularly tickled when he saw a sign reading "Please don't shoot the pianist" - he loved the idea of bad art meriting death!

- I'm not sure exactly what the Head lady does with that snake, but Scott has certainly given it a smug look. Almost as characterful as the profoundly demented gleam in the husband's eyes.

Page 3:

- I like the fact that Jerome, the younger cowboy, is remarkably ineffectual, and when the Head arrives, he goes into a flap and runs around waving his arms about. You could argue that while this subverts the stereotype of the capable cowboy, it plays into another one about the effete gay man. (His behaviour's in a similar vein to the chap who gets the spark in his hair in The Simpsons' gay steel mill.) The thing is, I'm pretty sure Wilde would have liked to play the role of hero to that sort of chap: he saw protecting the vulnerable but beautiful as his duty.

Page 4:

- There's a fair bit of 'Pygmalion' in Wilde's attempts to re-educate the Rolling Head: fitting, as Wilde was good friends with George Bernard Shaw (Shaw sensibly encouraged Wilde not to pursue a court case against the Marquess of Queensberry: Wilde, of course, didn't listen, it all backfired, and Wilde was jailed for homosexuality.)

And with that, I shall leave you with the words of Oscar

himself.

"Nothing that actually occurs is of the smallest

importance, apart from buying a print copy of the Journal here, or a digital one here."